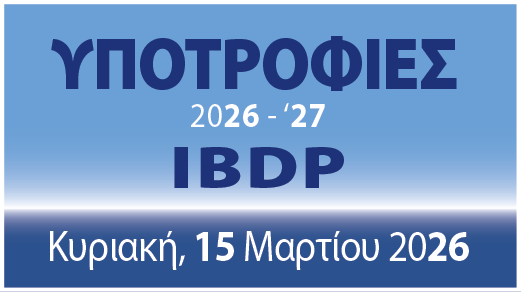

Core Subjects / Theory of Knowledge; Creativity, Activity, Service; Extended Essay

Theory Of Knowledge (ToK)

It is a commonplace to say that the world has experienced a digital revolution and that we are now part of a global information economy. The extent and impact of the changes signalled by such grand phrases vary greatly in different parts of the world, but their implications for knowledge are profound.

Reflection on such huge cultural shifts is one part of what the ToK course is about. Its context is a world immeasurably different from that inhabited by “renaissance man”. Knowledge may indeed be said to have exploded: it has not only expanded massively but also become increasingly specialized, or fragmented. At the same time, discoveries in the 20th century (quantum mechanics, chaos theory) have demonstrated that there are things that it is impossible for us to know or predict.

The ToK course, a flagship element in the Diploma Programme, encourages critical thinking about knowledge itself, to try to help young people make sense of what they encounter. Its core content is questions like these: What counts as knowledge? How does it grow? What are its limits? Who owns knowledge? What is the value of knowledge? What are the implications of having, or not having, knowledge?

What makes TOK unique, and distinctively different from standard academic disciplines, is its process. At the centre of the course is the student as knower. Students entering the Diploma Programme typically have 16 years of life experience and more than 10 years of formal education behind them. They have accumulated a vast amount of knowledge, beliefs and opinions from academic disciplines and their lives outside the classroom. In TOK they have the opportunity to step back from this relentless acquisition of new knowledge, in order to consider knowledge issues. These include the questions already mentioned, viewed from the perspective of the student, but often begin from more basic ones, like: What do I claim to know [about X]? Am I justified in doing so [how?]? Such questions may initially seem abstract or theoretical, but TOK teachers bring them into closer focus by taking into account their students’ interests, circumstances and outlooks in planning the course.

ToK activities and discussions aim to help students discover and express their views on knowledge issues. The course encourages students to share ideas with others and to listen to and learn from what others think. In this process students’ thinking and their understanding of knowledge as a human construction are shaped, enriched and deepened. Connections may be made between knowledge encountered in different Diploma Programme subjects, in CAS experience or in extended essay research; distinctions between different kinds of knowledge may be clarified.

Creativity, Activity, Service (CAS)

Creativity (Arts and other experiences that involve creative thinking)

Creative activities should have a definite goal or outcome. They should be planned and evaluated like all CAS activities. This can present something of a challenge where, for example, a student is a dedicated instrumental musician. It would be artificial to rule that something that is both a pleasure and a passion for the student could not be considered part of their CAS experience. How, though, can it help to fulfill CAS learning outcomes?

Perhaps the instrumental musician can learn a particularly difficult piece, or a different style of playing, in order to perform for an audience. The context might be a fundraising activity, or the student might give a talk to younger children about the instrument, with musical illustrations. Appropriate CAS activities are not merely “more of the same”—more practice, more concerts with the school band, and so on. This excludes, for example, routine practice performed by IB music or dance students (as noted earlier), but does not exclude music, dance or art activities that these students are involved with outside the Diploma Program subject coursework.

Activity (Physical exertion contributing to a healthy lifestyle)

Similar considerations apply here. An outstanding athlete will not stop training and practicing in order to engage in some arbitrary, invented CAS physical activity. Setting goals, and planning and reflecting on their achievement, is vital. “Extending” the student may go further, for example, to asking them to pass on some of their skills and knowledge to others. If their chosen sport is entirely individual, perhaps they should try a team game, in order to experience the different pleasures and rewards on offer.

Service (An unpaid and voluntary exchange that has a learning benefit for the student)

It is essential that service activities have learning benefits for the student. Otherwise, they are not experiential learning (hence not CAS) and have no particular claim on students’ time. This rules out mundane, repetitive activities, as well as “service” without real responsibility. A learning benefit that enriches the student personally is in no way inconsistent with the requirement that service be unpaid and voluntary.

It is essential that CAS activity is an extension to subject work. To attempt to count the same work for both a subject or extended essay and CAS would constitute malpractice.

Where to start: It is the responsibility of the school to guide and help students towards the completion of a challenging and life-changing CAS programme.

A team approach will be followed where CAS advisers (under the direction of the CAS coordinator).

- provide advice and support throughout the whole CAS experience (helping students set goals and develop their skills of reflection)

- make the necessary contacts with activity supervisors & organisations

- ensure the regular updates of students’ records & diversity in the activities they undertake

- are available & accessible to clear up any confusion

Extended Essay

The Extended Essay is a 4,000 word research paper that each IB Diploma Programme student has to write on a subject of their choice.